Security forces in Venezuela have killed a string of infamous gang bosses, indicating that the gangs are no longer operating with impunity as they have for years, though some have managed to avoid the crackdown.

By InSight Crime

Mar 3, 2022

The latest gang leader to be killed is Darwins José Vizcaíno Guerra, alias “El Curí,” who died in a shootout with soldiers from the Bolivian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana – GNB), El Pitazo reported.

The firefight occurred February 22 along Troncal 10, a highway linking Venezuela’s northern states of Monagas and Sucre. Estimated at about 60 members, El Curí’s gang controlled villages along that highway, extorting, robbing and hijacking vehicles and cargo trucks that passed.

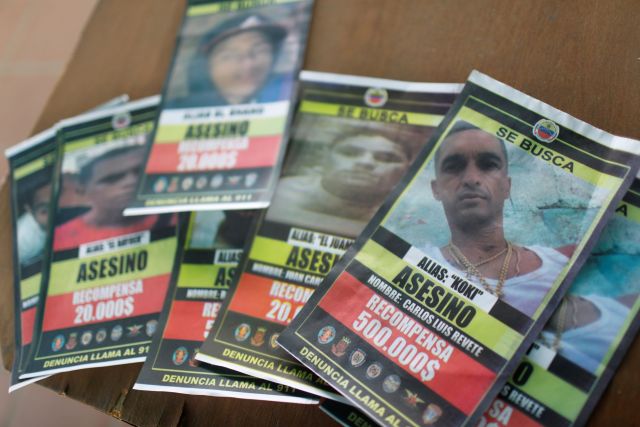

The killing of El Curí came just weeks after the country’s most notorious gang boss, Carlos Luis Revete, alias “El Koki,” was shot dead in a police operation. El Koki was killed February 8 after a three-day manhunt in a mountainous area outside of ??Tejerias, in Aragua state.

Late last year, a massive operation took place against another notorious gang, Tren del Llano, which migrated from the central state of Guárico to the coast of Sucre, where the group assumed control of trafficking drugs to nearby Caribbean islands. Security forces killed more than 17 members of the gang in the November 2021 operation, including its leader, Gilberto Hernández, alias “El Malony,” according to locals who spoke to the media.

Officials in Venezuela signaled this month that authorities had launched a plan to target the country’s gangs, some of which have grown so large that they are known locally as megabandas, or megagangs. At the February 17 session of the country’s National Assembly, Interior Minister Remigio Ceballos told legislators that “we have identified all the criminal gangs in the country, and we are going to combat them.” Ceballos, however, did not provide details about the plan or clarify whether the recent gang boss shooting deaths were a result of it.

InSight Crime Analysis

Authorities attacking some of the country’s most powerful gangs in such a short period of time demonstrates a drastic shift in the government’s tolerance of the groups, and the regime of President Nicolás Maduro may be using the offensive to bolster its reputation and regain control of previously ceded territory.

The dismantling of the Curi gang is a prime example of this change. Since 2019, the gang had managed to take hold of traffic on the Troncal 10 highway, robbing trucks and extorting vehicles at will. Gang members were known to use the cover of nearby mountains to stage their operations but were not rooted from the area until months after a video circulated of the gang holding hostage an army sergeant, who pleads with the military, saying: “don’t mess with the population, these boys won’t mess with you.”

Other gangs have similarly found themselves under attack after years of impunity. Just three years ago, El Koki had such a stranglehold over the hillside district outside Caracas known as Cota 905 that he held a block party, where he could be seen on video smiling with a pistol in his waistband.

His grip on the neighborhood was facilitated by one of Maduro’s failed policies: the creation of so-called peace zones, or areas where security forces maintained little to no presence. But El Koki ran afoul of the government after he raided the nearby La Vega neighborhood and his gunmen opened fire on the police and intelligence service headquarters in Caracas. Authorities responded in full force, sending some 800 troops into Cota 905.

After the raid of his stronghold, El Koki went on the run until he was shot dead by police.

It’s unclear what led authorities to target the Tren del Llano gang, which had been behind criminal activities in Guárico since 2008 and managed to expand into Sucre in late 2020, conquering the coast of Paria. Rumors swirled among residents that the gang ripped off a drug shipment or kidnapped the wrong person. Whatever the reason, the government deployed a 500-strong security force to destroy the gang.

One common factor in all of the gangs targeted is that they appeared to have drawn national attention.

Meanwhile, criminal gangs like the Tren de Aragua, who have been more careful, less violent and maintain stronger ties within the national government, have so far been spared. That gang’s criminal activities and operations center in the Tocorón prison are open knowledge.

Cracking down on violent groups may help Maduro promote the sense of security and governability needed for him to regain the support of Venezuelans. Maduro has lost much of his political base, as the results of the latest regional elections demonstrate.

The targeting of certain gangs also creates power vacuums, where other actors more closely aligned with the government can fill the void. For example, the Barrancas Syndicate (Sindicato de Barrancas) has controlled for at least a decade parts of the Orinoco river, which flows into the Caribbean and Atlantic Oceans. Yet the group was confronted by security forces in January after a conflict with Colombia’s National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN), which has sought to take control of the territory.

It would not be the first time the government has tried to manipulate such conflicts to its own advantage. For example, the Colombian guerrilla force invaded the gold-mining region of eastern Bolívar. The ELN incursion occurred just as Venezuela’s security forces went in to oust entrenched gangs.

…

Read More: InSight Crime – Is this the end for Venezuela’s Megagangs?

…